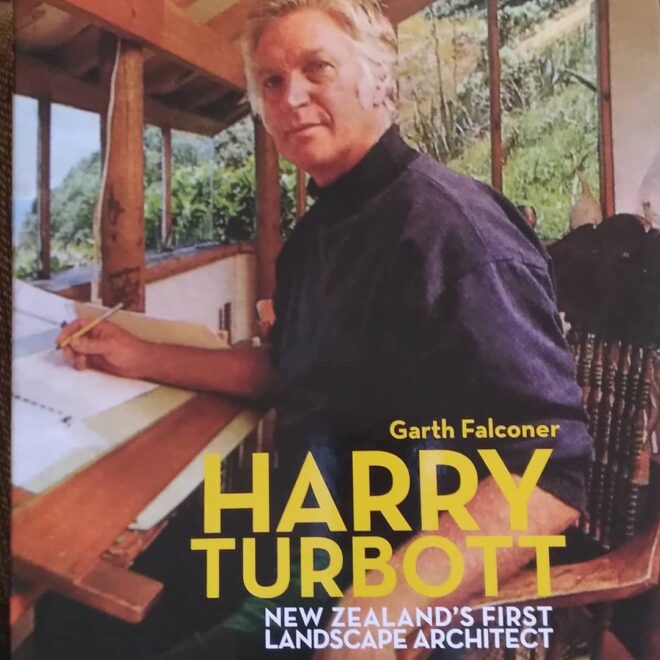

Garth Falconer, Harry Turbott: New Zealand’s First Landscape Architect, Blue Acres Publishing, 2020, ISBN 9780473 517496, 223 pages

Garth Falconer, Harry Turbott: New Zealand’s First Landscape Architect, Blue Acres Publishing, 2020, ISBN 9780473 517496, 223 pages

This is a ground-breaking book about New Zealand’s first qualified, teaching landscape architect, the first to establish a multiple-person landscape architecture office and to work the length and breadth of that country. It is fascinating, both for the wider world context of his training and travels and as an overview of his career and contributions to the industry and to New Zealand. It’s a very welcome book.

Author Garth Falconer is a landscape architect and urban designer, who studied under Harry in the post-graduate landscape architecture course at Lincoln University, in 1986. I did the same a few years later but sadly not with Harry.

Turbott’s father, Harold Bertram Turbott, was a missionary in China and a doctor. On his return to New Zealand he contributed much to regional Maori health services. He made national radio broadcasts from 1943 to1984 and was elected President of the World Health Organization in 1960. Due to an affair of his father’s, his parents divorced in 1935 and his mother Eveline took Harry and his sister to Auckland, raising them alone. Tough start.

Harry started work after high school as a draftsman in Gummer & Ford architects’ office, New Zealand’s leading practice, which had major projects in all the regional capitals. William Gummer had worked with Edwin Lutyens in England and Daniel Burnham in Chicago: both leading architects, with interests in garden design and the City Beautiful movement. Formative work experience.

In 1954, Harry graduated with distinction from the School of Architecture, Auckland University College, University of New Zealand with a Diploma in Urban Valuation. He worked for two years as a contract designer for several architects, mostly on houses and alterations ‘for the rich’. And he met the love of his life, artist Nan Manchester, via the university tramping (bushwalking) club. She was teaching art at Epsom Girls Grammar.

In the same year they both won travelling scholarships: she to paint in France and Spain; he to study world architectural masterpieces. Harry looked not to England, but the United States and the landscape architecture program at Harvard, in Massachusetts. Its Graduate School of Design (GSD) offered four programs: architecture, landscape architecture, city and regional planning. Harry’s was a Fulbright Scholarship, providing the funds to go. He and Nan married and left by ship in 1957.

GSD Dean was Josep Lluis Sert, a famous Catalan architect; American landscape architect Hideo Sasaki was Associate Dean. Another famous professor there was British architect Serge Chermayeff. The timing was good: Harvard was rebuilding facilities, attracting world-leading thinkers and designers. Frank Lloyd Wright gave lectures at MIT (just down the road) as did Finn, Alvar Aalto (Harry’s heroes, both). A stimulating hothouse for an ambitious young designer!

Harry spent a year cramming a two-years’ post-grad Masters course into one, and a second doing work experience with the ‘absolutely mad’ American landscape architect, Dan Kiley, in wooded Vermont, on a farm near the Canadian border. Kiley worked on only four or five projects at a time, but each was big, with leading design teams (e. g. Eero Saarinen, architect) and huge budgets. One project was the third block of Independence Mall in Philadelphia: a major urban renewal of vacated city cores. Such jobs were becoming fashionable.

The newly weds used savings to travel to England. After five months, they bought a VW Kombi and drove across Europe in 1959–60, visiting chateaux landscapes of Andre le Notre such as Versailles, modernist works by Le Corbusier in Ronchamp and Marseilles, on to southern Spain for six months, through Greece, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and to India, for three months. New Delhi with its grand design by Lutyens was now 30 years old, and Le Corbusier’s new work at Chandrigarh was India’s first post-independence capital. Harry was getting un-impressed with foreign experts imposing designs without consulting the local people who would build, use and have to live with them. They boarded a NZ ship in Calcutta and travelled, with Kombi, back to Aoteoroa, arriving in 1961.

A part-time teaching job at Auckland University’s architecture school allowed Harry to teach landscape architecture, albeit site and garden design, and build his design practice. New Zealand was echoing America in smaller ways: there were plans for Auckland’s first high-rise, motorways for high-speed car travel, with old neighbourhoods being destroyed for growth. Nan lectured at Elam School of Fine Arts and both joined the local arts community. They rented a house at Karekare Beach, remote from the city, on the district’s wild west coast.

Harry’s design practice grew in the 1970s, strengthened in scope in the 1980s and gained recognition in the 1990s. In 1994 the NZ Institute of Architects gave Harry’s Becroft House its 25-year award as outstanding and enduring architecture. Over the decades his jobs included Auckland and Christchurch motorway landscaping (this was pioneering work that influenced engineers and project managers); working on institutions such as Auckland’s Museum of Transport and Technology, the University of Otago in Dunedin and shopping centers such as Pakuranga in Auckland. He was first to do infrastructure works in national parks. These were modest in scope: parking areas, walks, lookouts, toilet blocks, but also a critical ‘interface’ of visitors and environment. Harry worked on West Auckland’s forested Waitakere Ranges (the large Arataki visitors’ centre, tucked into the forest edge), Tongariro National Park and Turoa ski field, Maungawhau (Mt Eden)’s volcanic cone. He humanised the landscape around the Freemans Bay council flats and converted a former Pumphouse in Takapuna into a theatre and arts complex.

A significant project was Harry’s work at Waitangi – the national site of the signing of New Zealand’s Treaty with the Maori peoples. In 1974 he worked on the new Visitors’ Centre (after John Scott’s design was ruled too expensive) and in 1976 designed a Whare Waka (canoe house), paying respect to traditional Maori design and protocol. In the 1990s he designed a circular boardwalk from the visitors’ centre to Treaty House, which he described as the ‘backbone of the Waitangi experience’, tying together the wetlands, forest restoration, the waka and Te Whare Runanga (carved meeting house).

Harry also worked overseas, building resorts in Fiji in the 1970s and in the 1980s, through his friend Dr Mary Herdson, he discovered Taputapuatea marae on Raratonga. This had been a sacred tribal gathering space, with the Para-o-Tane Palace, a large two-storey Georgian house, then in ruins, that had previously been the focus of the local tribe. Harry did research, made measured drawings and got the backing of Auckland University architecture school to provide student labour. Four years’ worth of student holidays saw staged restoration, re-roofing and site works. This was a passion project and an effort towards cultural reconciliation. The palace and gardens re-opened in 1993 with rejoicing and much pride.

Harry retired from teaching in 1998 but kept working into the 2000s, winding down slowly. In 2005 Unitec landscape architecture lecturer Matthew Bradbury presented a paper at the NZ Institute of Landscape Architects’ conference titled Harry Turbott, landscape modernist. He focussed on three core areas: concern for the environment; the centrality of the user in any design; and integration of architecture and landscape. The paper cited Harry’s Mimiwhangata Coastal Park (a low-key Northland resort) as the first integrated landscape/ecological study in New Zealand, and Arataki Visitors’ Centre as an important attempt to work with First Nations culture through architecture and landscape.

What strikes me about this biography is the breadth of work, humility and skills of Harry and Nan, which served to increase ties in New Zealand to Maori, Pasifika and the natural environment. The house they designed, built and lived in at Karekare alone is a masterful, quiet melding of place and people.

Falconer’s book has four parts about Harry: life history; North American connections; his greatest hits (24 of them); and recollections of Harry by significant others. A fifth remembers Nan Manchester, a remarkable artist and force in her own right.

I learned much about American environmentalism infiltrating the New Zealand mindset. Would that we had other monographs on pioneers in landscape architecture: this one shows the way. It has much to say on cultural melding, environmental and cultural sensitivity and listening, as much as ‘speaking’, in design. More, please.

More info such as an interview with the author, at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/nights/audio/2018770344/harry-turbott-new-zealand-s-first-landscape-architect

RRP NZ$75 (plus shipping – for cost to Australia, contact Garth at his studio): https://reseturban.co.nz/connect/ or email: studio@reseturban.co.nz

Reviewer: Stuart Read