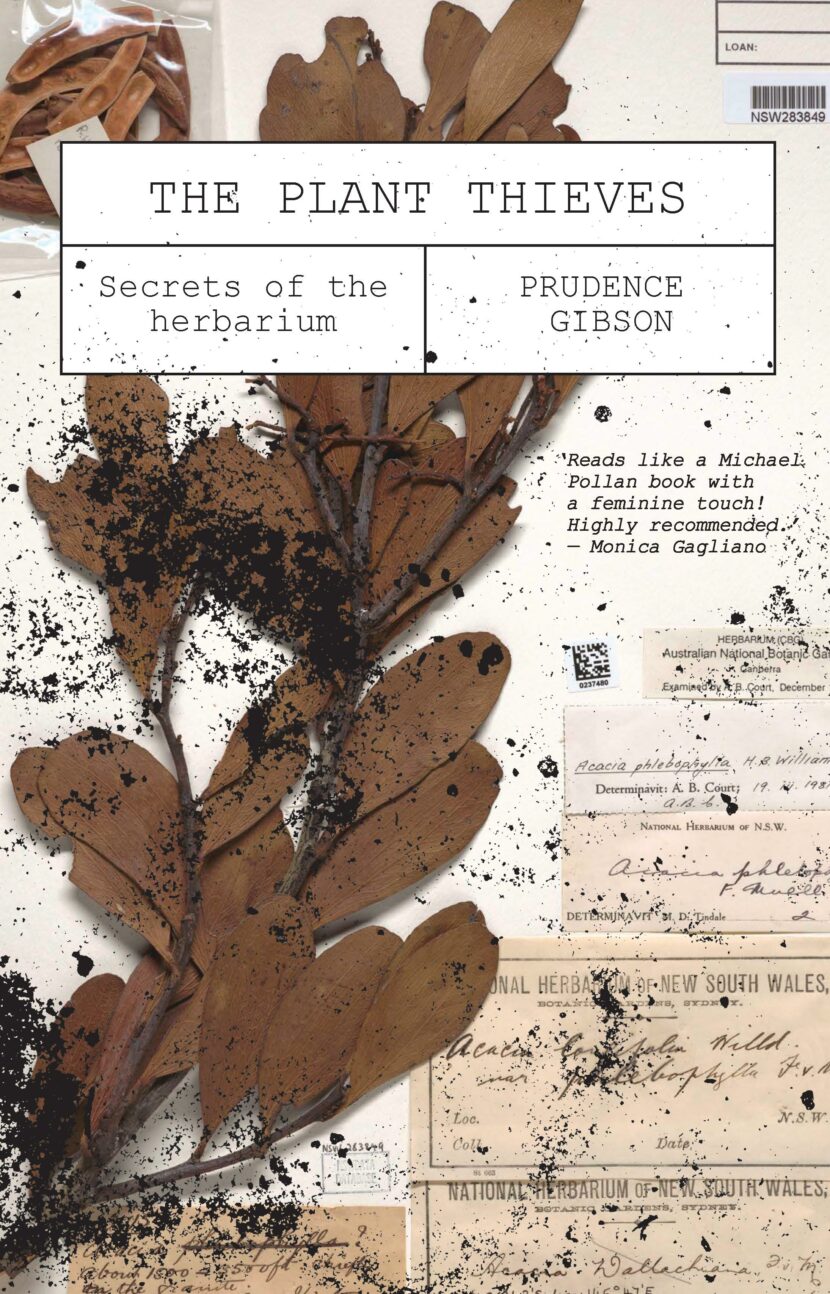

Poppy Fitzpatrick reviews The Plant Thieves: Secrets of the Herbarium (NewSouth, 2023) by Prudence Gibson.

This book takes us on a journey of unexpected discovery. What begins as a seemingly simple interrogation of the collecting and cataloguing of plants within the National Herbarium of New South Wales – which is fascinating in and of itself – slowly leads us up a complex network of garden paths. We meet unique characters from both the flora and fauna worlds, peek inside illicit plant communities and uncover the brutal histories hidden behind many of the plants that surround us in modern life.

Dr Gibson, a research academic in plant studies at the University of NSW’s School of Art and Design, approaches her visits to the Herbarium with a sense of wonder that exudes from every page. She assigns each specimen a personality that brings a deeper narrative to the science and an opportunity to respond to the plant world with an empathy often reserved for fellow homo sapiens. This perspective challenges the prevailing Western, hierarchical scientific view and encourages a re-evaluation of our relationship with the plant world. Gibson proposes a vision where humans and nature coexist as equals, championing First Nations knowledge and cultural connection to the land. What if we were to see the plant world not as something separate to us, but rather an extension of ourselves, something we are connected to in more ways than we can consciously comprehend?

It’s these questions that take Gibson on adventures beyond the Herbarium – from jumping into the water on Sydney’s foreshore to observe the kelp ‘waving its golden locks’, through to top-secret tours of exotic psychoactive cacti gardens inside the city’s inner suburbs. By presenting plants as individuals with nuanced personalities and rich personal histories, she prompts readers to question the way we exploit and interact with them. Should plants be recognised as independent beings with legal rights and agency over their own futures? At what point does collecting become thieving?

We’re told stories about particular specimens that contrast charming childhood memories with dark colonial truths. For instance, Luke Patterson, a Gamilaroi man, poet and academic working and living on Gadigal land, reminisces on his childhood among the coastal bushlands of Kurnell at Kamay – otherwise known as Botany Bay. His memories of collecting dried banksia cones for ‘wars’ with his cousins are fondly intertwined with cultural and place-based connections, but they also reveal the shadows of colonial folklore. As a reader I am now acutely aware that this revered native plant, named to honour botanist Joseph Banks, hides some of Australia’s darkest history in plain sight. Although Banks’ vast specimen contributions are valuable to our herbarium collections and botanical sciences, they also represent a devastating period of Australian history when our ancestors pillaged the Asia-Pacific region on behalf of imperial Britain. The large absence of Indigenous knowledge in the collection and naming of native plant species is a powerful reminder of the broader social, political and cultural erasure of First Nations peoples. The banksia is just one example. Such stories have led me to perceive the vegetation in my own local area with a newfound awareness of their often-murky history, and the complex interplay between beauty and brutality.

In an unexpected turn, we are introduced to psychoactive plant life. Gibson considers the benefits from, and concerns about, the consumption and cultivation of these plants – many of which are fiercely protected by those who grow and use them. Here she exposes the constant flux between conservation, culture and spirituality; medicine, law and science – no area left untouched, and nothing a simple black and white answer.

A harmonious interplay between art and science guides us through the book. Filmmakers, painters, and poets, alongside Gibson’s own observations and anecdotes, interpret specimens from the Herbarium. The fusion of creativity with science serves as a powerful reminder of the deep interconnectedness of all things – a truth often overlooked in Western culture. I closed this book with a renewed sense of wonder at the natural world, and the quiet power plants hold over us as human beings. Who is really in charge?

Poppy Fitzpatrick is a writer, photographer and filmmaker living on Kaurna Country in Adelaide, South Australia.