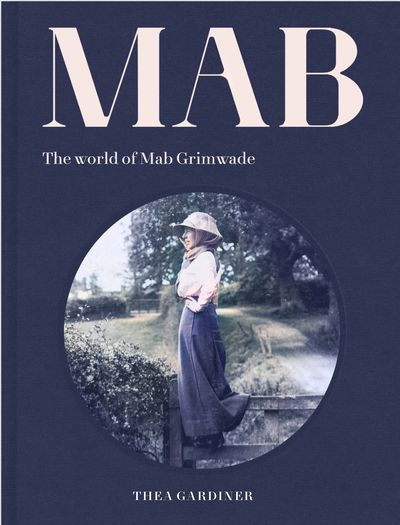

Sandra Pullman reviews Mab, The World of Mab Grimwade by Thea Gardiner (The Miegunyah Press, Imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2023)

This beautiful book celebrates the life of Mabel Louise Grimwade née Kelly (1887–1973). The author, Thea Gardiner, gives the reader a fascinating insight into the elite world of the Kellys and Grimwades, who made their money from mining and pharmaceuticals.

Mabel (Mab) Grimwade was amazing and it is refreshing to read about a woman whose achievements were as impressive as her husband. Mabel was born into Melbourne’s establishment. Her life was one of privilege, private education, country houses, mixing with a small select group of people, and she carried out the social expectation of the time by marrying – in 1909 Victorian chemist, botanist, industrialist and philanthropist Russell Grimwade (1879–1955).

Writing biographies of women is challenging as, more often than not, women’s personal papers are disregarded because of the misplaced and biased view that they contain nothing of value compared to men’s lives and accomplishments. This is the case with Mab Grimwade. Interestingly, Gardiner believes Mabel was the architect of the scarcity of personal papers, thus deliberately controlling what the public knew about her. What did Mab Grimwade not want the public to know? Disappointingly Gardiner does not explore this intriguing question.

Moreover, without personal papers, she is handicapped. What is appealing about this book is how Gardiner compensates by including the social context of the day in each chapter, which explores a separate aspect of Grimwade’s life from her childhood and marriage to travelling, playing golf, gardening, growing roses, as well as importantly her philanthropy and charity work. Gardiner also uses mostly black-and-white images to capture a sense of the era. Perhaps, however, a few more coloured pictures, if they existed, would have been preferable to some of the poorly reproduced garden images.

While Mab and her set were not tied up in the mundane chores of housework and had many freedoms, they were bound by the social expectations of domesticity, that is managing the household. Outside employment was out of the question. To overcome the lack of meaningful challenges in their lives, these elite women cleverly used philanthropy and charity engagements as a subterfuge. Innocent tea parties, fashion and dog shows raised money but also developed the organisational and leadership skills of those involved, which they put to use in institutions including the Fitzroy Mission Free Kindergarten movement, National Gallery Society of Victoria and the Royal Horticultural Society of Victoria. While some may have abhorred filling the void with social events, Mab Grimwade seems to have relished this lifestyle.

Mab was not a feminist, even if she did not strictly adhere to the gendered roles expected of her class. Her interests were eclectic and several were unfeminine. She managed her money and investments, enjoyed driving cars, smoked, which was terribly un-lady like, and played golf and cricket. In 1905 she captained an all-girl Montalto cricket team called Toorah, and later, due to her outstanding ability as a first-class cricketer, was elected president of the all-male Yarraville Cricket Club.

The last chapter is rather special as it explores Mab’s love of gardening, especially growing roses at her city home Miegunyah in Toorak and country property Westerfield at Baxter. Not many people have a rose named after them by the distinguished rose breeder Alister Clark – unless you are a society woman like Mabel Grimwade. The ‘Mrs. Russell Grimwade’ or ‘Mab Grimwade’ rose was a sport of Clark’s Lorraine Lee, discovered at Westerfield and which Russell Grimwade registered with the National Rose Society of Victoria in 1937. It was described as a hybrid tea, with a confusing list of flower colours ranging from pale pink to orange or yellow.

Both Mab and Russell were involved in the design of their gardens, along with Edna Walling, Ellis Stones, EF Cook, John Stevens and WH Griffiths. Both became keen on Australian plants and felt they were important to preserve. At Westerfield, Grimwade planted 50 varieties of eucalypts along with other medicinal plants. As a biochemist and investor, he was interested, especially during the 1940s, in the essential oils and extracts.

As with the other chapters, Gardiner includes context, writing about the different garden design styles popular during the 20th century. The gender issue raises its ugly head again. Despite women being involved in their gardens, the ‘average home gardener’ was considered male because they had the strength and scientific knowledge deemed beyond women’s reach.

As a serious gardener, Mab Grimwade was a member of the Royal Horticultural Society of Victoria (RHSV). Her achievement there was to cement the smaller societies under the umbrella of one governing authority, the RHSV. She was also a member of the Society for Growing Australian Plants and Native Plants Preservation Society of Victoria, an indication of how much she valued our unique Australian flora.

Mab, The World of Mab Grimwade is a fascinating insight into a woman who in some ways was ahead of her times but was also comfortable not causing too many ripples. With a strong social conscious, she used her position to quietly improve the lives on many people on many different levels. I recommend this book to all those interested in women who shaped 20th-century Australia.