Book review by Tim Gatehouse

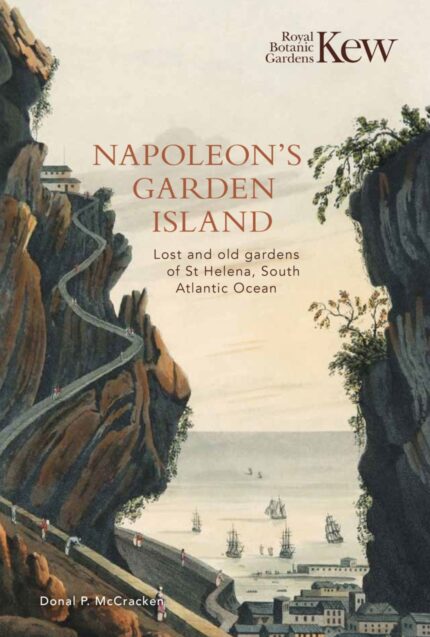

In Napoleon’s Garden Island – lost and old gardens of St Helena, South Atlantic Ocean (Kew Publishing), Professor Donal P McCracken dispels the common perception that the island of St Helena is only significant as Napoleon’ place of exile.

Despite its diminutive size of only eight by 16 kilometres and isolation in the South Atlantic Ocean, St Helena has a remarkably diverse endemic and exotic flora and a rich horticultural heritage. The island’s subtropical climate, volcanic soil and wide variations of altitude have contributed to the rich variety of its plant life.

Uninhabited when discovered by the Portuguese in 1502, St Helena was not permanently settled until 1657, when the English government granted it to the East India Company. Having a monopoly of trade with India and the East, the company gained control of most of the sub-continent and other trading posts throughout the East. St Helena was a convenient way station for the company’s fleets sailing to England from India, China and South Africa. It flourished as a military outpost during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1836, after powerful British merchant interests induced the government to curtail the company’s trade monopoly, governance of the island was transferred to the Crown. After the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the advent of steam ships, which provided a faster route to India, St Helena declined in importance.

Against this historical background, the author explains the origin, development and decline of the public and private gardens of St Helena. He shows how the present landscape of the island has been created by its history, and the reasons for the existence of a rich exotic flora. These imports now threaten to overwhelm the unique and fragile endemic plant life of the island, described by Sir Joseph Hooker as ‘a fragment from the wreck of an ancient world’. The indigenous flora suffered badly from the effects of settlement, much of the woodlands and other plant life being destroyed for building and fuel by settlers and by the livestock they introduced. For Napoleon enthusiasts it is pleasing to note the attention given to the island’s most famous gardener and to his restored garden at Longwood House.

St Helena’s gardens

Other factors contributed to the richness of St Helena’s flora, also in conjunction with its importance in provisioning the East India Company’s ships in transit to Britain. A mania for botany swept Britain from the late 18th century, coinciding with the expansion of the empire. This made a wider range of exotic plants available to British collectors and resulted in an increase in the publication of botanical works. Many specimens found their way into the island’s gardens. The high salaries and subsidies paid by the East India Company in recognition of the island’s importance to its trading activities provided the means to establish notable public and private gardens.

The public gardens were largely the creation of enlightened governors who shared the botanical interests of the elite in Britain. The Castle Garden in Jamestown was initially planted for food production but later used for the acclimatisation of plants coming from the East to Britain. Here they could be revived after the rigours of the voyage; experiments in propagation were also made. Subsequently it became a public pleasure garden, which it remains today with much of its original layout intact. In 1787 the Botanic Garden was established. Exotic plants, including potential cash crops, were trialled in the garden; indigenous plants were scientifically studied; and specimens sent to Kew. After the transfer of the island to the Crown, the garden was not maintained. The site is now occupied by residential buildings. Another botanic garden and arboretum were planted around Plantation House, the governors’ residence. This survives in a diminished state.

Other substantial gardens and arboreta were planted on many of the small estates of company officials and settlers. The gardens of this closely knit gentry class contained rich varieties of exotic plants. Some also became sanctuaries for threatened indigenous species.

Once the East India Company lost control of the island, most of the company’s officials were dismissed and their estates became derelict. An attempt to produce a cash crop by the introduction of flax succeeded for a short period, although its prolific growth took over large areas of the island, smothering all other exotic and indigenous flora. Other environmental damage from earlier times is evident in the bare cliffs above Jamestown and the treeless plateau around Longwood.

One of the advantages of the Crown’s parsimoniousness is that little unsympathetic development took place after the transfer. Jamestown and several old Georgian farmhouses in the hilly interior of the island survive in picturesque settings, as do Plantation House and Longwood. In recent years a determined conservation movement has developed with the cooperation of Kew Gardens. The overgrown gardens of ruined houses have retained rare species and many indigenous plants are now being saved from extinction.

Napoleon’s Garden Island offers a narrative with detailed endnotes and appendices that will appeal to readers whose interests in horticultural history are general or specialised. The text is generously complemented by colour plates and integrated illustrations. The book does justice to this small island, which has been described as a global botanic garden.