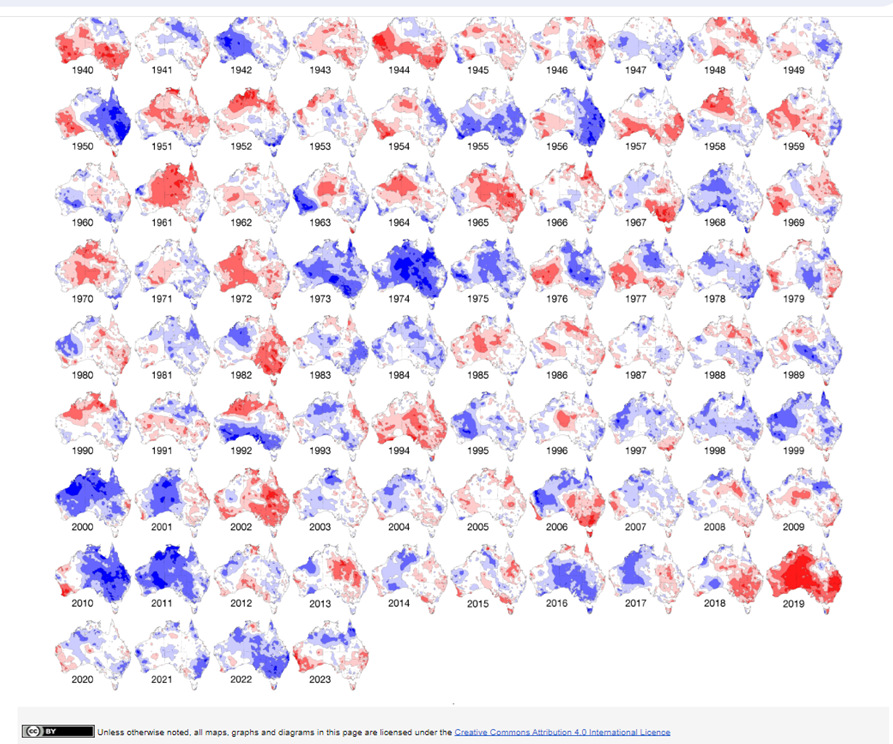

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology publishes historical data about the climate in Australia, including maps ranging from the most recent day, back to 1900 for rainfall and 1910 for temperature, http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/maps

I doubt whether there are many gardeners left who aren’t firm believers in climate change, in part from anecdotal experiences in their own gardens. I used to run into the occasional old timer who, no matter how bad you thought it was, would always say, “You think it’s bad today, you should have seen how bad it was in the summer of ’39!”. They were probably right: there had been worse seasons in the past but that was until December 2019 and January 2020 when most records were broken. Both examples, however, illustrate to me what I fear most about climate change.

Climate change will inevitably have effects on our garden plants but to a large extent it will be modified when compared to those experienced by plants in the wild. For plants to be in a stable environment, everything has to be perfectly balanced over time. As an example, despite having vastly different metabolic rates at different times of the year, evergreen and deciduous oaks in northern Mediterranean regions exist in reasonably stable numbers. Obviously local factors can change the mix but, overall, the variety of species will stay much the same and in similar numbers. Nevertheless, in the wild, a small change in climate such as the small increase in average temperature we have already seen, will alter the balance favouring one plant species over another, leading to winners and losers. Certain species will increase in numbers and others decrease or even potentially disappear.

Our gardens are different. In a garden most plants and especially selected favourites are protected from minor environmental fluctuations; survival of the fittest does not always occur. We all know what happens when we go away for a while, weeds and creepers take over, often displacing the things we want and, without pampering, some of our treasures can be lost. The garden environment is modified: water and extra nutrition is provided when needed, sensitive plants are protected from the sun, cold and wind, and weeds and plants that would take over given half a chance are controlled or removed. This balance is only maintained with our intervention.

Even so, the ability for us to modify the environment successfully is not limitless and that is exactly what the droughts of 1939 and especially 2019/20 exemplified. For our gardens it is not the predicted increase with climate change in mean temperature of 1.5-2.0º C that is important, it is the predicted more frequent and severe extremes of weather that will test our ability to garden with the same plants. The last five years have been a good case study for me, and I’ll now cover some of my observations over those years of my property, which is about two km out of the town of Mittagong in the Southern Highlands of NSW. We are not on town water.

During 2019, the extremes of the heat and dry tested most plants. Many people think that Australian native plants, having developed sclerophyllous adaptations, are immune to whatever climate is thrown at them. Unfortunately, that is not the case and many native species struggled and died throughout the local bush and in our gardens during that time. We lost a Eucalyptus smithii estimated at over 200 years old, which showed no evidence of disease, just water lack. Unfortunately, as a severe drought reaches its peak, several other things occur. Record high temperatures are experienced and the higher the temperature, the greater the soil and plant water losses. The air humidity falls to single digits and plants may be unable to maintain hydrostatic pressures in their leaves and stems resulting in wilting and stem die back. Just when plants need a lot of supplemental water, dams are low, bushfires are raging and water restricted.

Drought is not the only potential extreme weather condition we may encounter. After the drought broke in early 2020, we had some of the wettest years, ever culminating in 2022, which had more than twice the average annual rainfall. “Eureka” you might be thinking but again too much of a good thing can be just as difficult to manage. Many plants found themselves, often for the first time, in water-logged conditions for weeks to months. The drought tolerant Mediterranean plants we had enthusiastically planted to cope with the next dry spell, died in their masses, as did a number of established trees in newly sodden areas.

Acer species

So, what are the lessons from the past five years? I’ll use one of my specific plant interests, Acer (maple) species to illustrate, keeping in mind as a collector I will continue to try with species that need an inappropriate amount of care to survive. Maples are shrubs or small trees that originate from northern hemisphere temperate regions with distinct seasons. They are therefore mostly deciduous though some evergreen species extend into the subtropical regions of Asia. The majority come from areas with adequate rainfall of >800 mm rain annually and grow on the edges of forests. In Australia these conditions are best replicated in the elevated regions of the southeast and Tasmania. The pity is that these areas are also bushfire prone, so valuable collections could be lost overnight. Though some maple species do come from around the Mediterranean and may be better suited to areas of Australia, e.g. Acer monspessulanum, overwhelmingly the most popular in our gardens are the so-called “Japanese Maples”, cultivars of Acer palmatum and closely related species.

In Japan they live in a humid environment and would receive more than 1000 mm rain per year, predominantly in summer, often over 1500 mm. You can see, therefore, that in southeastern Australia, even a mild drought could cause water stress. They are also forest trees, so planting them out as specimen trees in direct sun is inadvisable. Even so, maple species and cultivars were not affected equally during that hot dry summer of 2019/2020 and certain Japanese maple cultivars fared better than others. Most adversely affected were those with larger, papery leaves. Conversely those with small leaves which included the dissectum group (weeping maples) which have thin lace-like leaves, tolerated the hottest of days with minimal damage. The same was true of maples from other regions of the world and those with small leaves generally survived with less damage. If they had larger leaves, the ones with glossy more leathery leaves stood up better to the hot days than those with thin papery leaves. By the end most did show signs of severe stress, with some die-back, smaller leaves than usual and a thinner canopy, as did every other plant I had. For some, their bark is a weakness. Those in the snake bark group such as Acer davidii, are particularly susceptible to sunburn as is also true of other trees with attractive but thin bark such as cherry trees (Prunus sp.). They both can develop deep wounds from the late afternoon sun if poorly positioned. These can take years to heal.

Let’s now move forward to what happened during the really wet years that followed. Initially everything that had survived quickly recovered, bouncing back better than ever. The next year we had a bumper crop of fruit, seed, cones, you name it. But then as the rain continued in torrents, a number of trees started to wilt, not just small ones but established trees which for the first time were in soils saturated for weeks on end. I think we lost nearly as many trees as during the drought. Of the maples, Acer palmatum and those Acer species and cultivars grafted onto Acer palmatum were worst hit. In the wild, though they may grow in moist climates, they don’t grow where the soils get saturated and only a few maple species tolerate swampy ground. Of those that do, Acer rubrum and Acer saccharinum and their cultivars (sold in Australia as “Lipstick” maples) are the best and, surprising, also tolerate the heat and drought just as well. Nevertheless, planning for a ‘once-in-every-100’ years deluge is not really feasible. In the end it may come down to luck with your plant and site selection.

On the other hand, there are several things we can do to plan for the average dry spell. We all make the mistake of choosing plants in the good seasons when everything grows: you would think we would learn that another drought is just around the corner. We should make more sensible plant choices but only planting safe options reduces the sense of achievement. Whatever we plant, to help mitigate the effects of drought, we need to reduce plant and soil water losses as extra watering isn’t always feasible or practical. The best way to reduce water losses are by mulching and plant protection. Though mulching helps reduce water losses from soils (it also keeps the soil healthier supporting invertebrate life), most losses from plants are from their leaves. On hot days, leaf water losses can be so great it just isn’t possible to be matched by replacement from the soil even if watering is possible. This is particularly a problem for newly planted shrubs with limited root establishment and those in exposed areas. They will need protection from direct sunlight, and I cover small plants with elevated squares of shade cloth. For many, planting under a canopy of trees is a better option but some still need the shade cloth covering as well. Despite that, there are limits and you can’t modify the environment sufficiently all the time. If the predictions of more frequent climate extremes becomes a reality, then plant selection in our gardens may be determined for us.

Simon Grant OAM, (Acting) President of The International Maple Society and Vice-President International Dendrology Society (Australia).

This article is one of a series prepared for a project, Antipodean historic gardens and climate change, partly funded by a grant from the international charity, the Historic Gardens Foundation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in as a member to post a comment.