Members of the Bloomsbury Group during a stay at Garsington Manor. From left to right: Ottoline Morrell, Maria Huxley, Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell (1915)

This 2024 summer in London, the Garden Museum is presenting an exhibition exploring the gardens of the Bloomsbury group. Gardening Bohemia: Bloomsbury Women Outdoors centres on writer Virginia Woolf and her garden at Monk’s House; her sister artist Vanessa Bell, whose garden and studio was at nearby Charleston; arts patron and photographer Lady Ottoline Morrell, who presided over Garsington Manor; and garden designer and writer Vita Sackville-West and the gardens she created with her husband, Harold Nicholson, at Sissinghurst Castle.

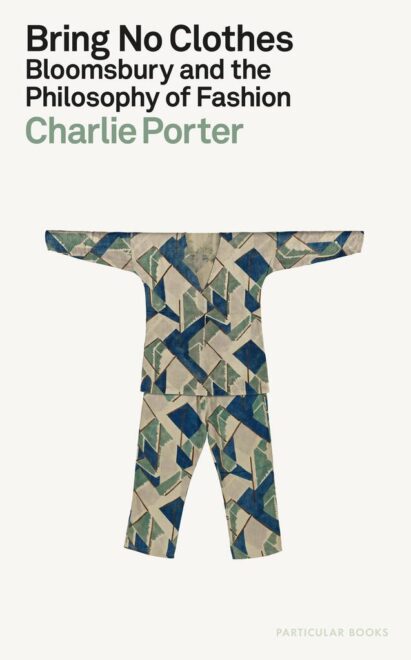

The exhibition has a catalogue Gardening Bohemia – Bloomsbury Women Outdoors by Claudia Tobin and comes not long after the publication in 2023 of Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion by British fashion writer, Charlie Porter. You can watch a talk by Charlie Porter on Tuesday 3 September (book tickets here).

Ahead of that talk, here is Trevor Nottle’s assessment of these two publications.

Each is significant because of the focus on the Bloomsbury group’s relationship to gardening. This is not always the green-fingered variety. Several members of the group were rather keen on bodily display and nudity, and on posing in garden settings. (Porter argues that this is in part because of the better light for photography outside than in dark interiors.) At the time, these antics were viewed as daring, provocative and rude, if not outright disgraceful, for members of the upper-middle classes who ought to have known better.

Each is significant because of the focus on the Bloomsbury group’s relationship to gardening. This is not always the green-fingered variety. Several members of the group were rather keen on bodily display and nudity, and on posing in garden settings. (Porter argues that this is in part because of the better light for photography outside than in dark interiors.) At the time, these antics were viewed as daring, provocative and rude, if not outright disgraceful, for members of the upper-middle classes who ought to have known better.

Across the group there were, as always, those who enjoyed posturing as a means of drawing public attention to their views – and to themselves. Others maintained a discreet distance from the scandals, while at the same time actively supporting the set with their money and their privileged privacy. Lady Ottoline Morrell and Victoria Sackville-West were two such Bohemian blue stockings who mothered the more outrageous performers, while at the same time managing to retain some façade of restrained aristocratic dignity. They too indulged their own whims and fancies as it suited them but almost always in the rigidity of class privacy that distinguished between ‘us’ and what ‘we’ do and the crude and very public behaviour of ‘them’ of the lower orders.

Throwing off conventions of dress, behaviour and class was all part of the new rage for being at the forefront of social progress. The illustrations in Gardening Bohemia offer an introduction to the spread of Modernism beyond the ateliers and galleries of the art world to the back yards, orchards and borders of country houses and cottages in remote villages and hamlets outside London, where frolicking and prancing naked were just fine so long as no-one but close friends saw the shenanigans. And who cared what the cook and the gardener thought of it anyway?

Charlie Porter brings a much tighter and more acerbic voice to his book. The intriguing title hints at nudity, display and the potential for shock. In fact Porter is looking for hidden stories, in particular the stories of homosexuality among the Bloomsbury women. He finds these in the garden. He also examines more deeply the role of domestic workers in the lives of the Bloomsbury set.

Here it all is − as explained by Porter – the floppy, wide-brimmed hats, the floor-length un-waisted gowns, the simple poke bonnets, the floating head scarves alongside the ‘bags of fruit’ worn by the men and the free-form bias cut rigs of the non-conformist chaps. Whether dressing up or dressing down, the Bloomsbury set made their mark; a mark that Porter brings up to date by his commentary that links that era with more thoroughly modern developments in the rag trade and in the expression of personal style as created by Vivienne Westwood, Zandra Rhodes and Porter himself.

What is interesting to gardeners are the links that become evident from reading both books. You realise that the Bloomsbury set were agents for change across many fields rather than single-minded exponents of one special interest. All considered themselves ‘other’: other than the mainstream; other than the ordinary; other than the predictable and other than the typical presented by the popular media.

As gardeners Morrell and Sackville-West expressed their otherness by rejecting the accepted styles and leads of Reginald Bloomfield, Thomas Mawson, the Pulham family, William Robinson and even Gertrude Jekyll. Both women made gardens that pleased them and their circle of friends. The gardens were broadly reflections of a much earlier time. At the other end of the Bloomsbury set, Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant created their own versions of gardens. These were wilder and more free than either Sissinghurst or Garsington Manor, the home of Lady Morrell, which remained private and unsung by the media. The expansive gardens of Sissinghurst and Garsington developed some similarities with the smaller gardens made by Woolf, Bell, Grant. Each, though, had their own version of a bright and vivid cottage garden with plenty of orange, yellow and red, and each had a casual feel with weeds and weedy plants given free reign.

Presenting the Bloomsbury set in this new light has been made possible by revisiting the evidence in written documents, and looking again with different eyes at photographs, paintings, as well as the surviving gardens themselves and those recreated in recent times.