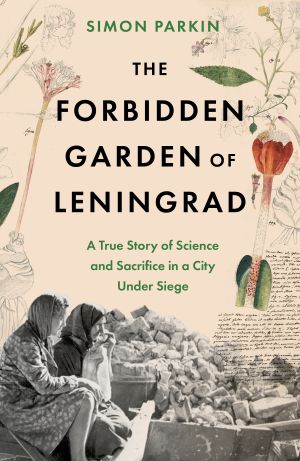

That is the question at the core of The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad: A True Story of Science and Sacrifice in a City under Siege by Simon Parkin (Hachette, 2024).

The story of the siege of Leningrad for more than 900 days during the Second World War has been told many times and, in a few cases, very well, such as that by Harrison Salisbury in The 900 Days. Parkin’s book is a ‘subset’ of that terrible event; at its centre it speaks to our times as well as to the concept of ‘garden history’.

Indeed the ‘hero’ of this story, though dead by the time of the central tragedy, is a flag bearer for the concept of great scientific practice and also a great scientist, who was surrounded by not only disbelievers but political spreaders of disinformation. Josef Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, better known as Joe Stalin, became personally involved in the vilification and then murder of the hero. Stalin, the ideological driver of the greatest excesses of the Soviet Union, seems now to be being ‘mirrored’ by the incoming President of the United States in his ability to pick weird ‘scientific advisers’ of no repute and put the welfare of his people at huge risk.

As most agricultural scientists with an interest in the history of their discipline, I have long been an admirer and follower of the work of Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943), the hero of this story. Vavilov was director of the V I Lenin All-Union Institute of Agriculture in Leningrad. He is regarded as the founding father of the concept of seedbanks, a huge idea in its own right. This came from his relentless search and study of the origin of species plants that were of profound importance for feeding the planet. Vavilov and his teams of men and women scoured the planet in the 1920s and ‘30s in search of the origins as well as wild relatives of everything from wheat, rice, maize, potatoes, many fruit crops and thousands of flower species. They brought them together to study and record, and most importantly to preserve in an orderly way in what we now call a seedbank.

The author of this book, Simon Parkin, who is a good and very accessible writer, traces the arc of Vavilov’s life and great scientific achievements from being an acolyte of the ideas of Darwin to seeking to feed his countrymen and stop the waves of starvation that swept through the new Soviet Union. Vavilov’s institute had a huge network of research sites scattered across the vast Soviet state but its centre and intellectual powerhouse was in a large and impressive building on the opposite side of the great square to the Hermitage. It was here that Vavilov drove a significant group of scientists, technicians, archivists and librarians to put together the world’s first seedbank. As their leader, he imbued in them a mission to try to identify the origins and then locate the likely relatives of all species of plants of value, both economic and as a food and fibre source for humans. In this they eventually pulled off some truly remarkable outcomes even though Vavilov (who was arrested in 1940 and imprisoned at a concentration camp at Saratov, where he died on 26 January 1943) and many of his colleagues paid with their lives. During the siege, people at the Institute chose to preserve its collection rather than touching any of the containers of rice, grain, lentils and beans that might have fed them and other starving Leningraders.

In his postscript, Simon Parkin poses existential questions:

…beneath the surface of a simple tale of choice and cost, sit a cluster of more taboo questions: what sacrifices are permissible in the pursuit of scientific progress? At what point should a person choose to disobey a directive? What responsibility do we each have to the survival of future generations, and what is the correct course of action when that responsibility sits at odds with our obligation to the living?