Do you want to know what a florilegium is, or a herbal, and would you like to acquire a piece of an undisputed monument in this genre of books? If so, you could be looking for Johann Wilhelm Weinmann’s Iconography of Plants and Flowers to the Life, or Conspectus of some Thousands of Plants, Trees, Shrubs, Flowers Fruits, Fungi, etc both Native and Foreign. But be aware: this publication consists of four (or sometimes eight) folio volumes, the first appearing in 1737 with a commentary in Latin (then the language of the learned) and German. It was compiled by a Bavarian apothecary, Johann Weinmann (1683–1744), who was probably the first to use a colour mezzotint method of engraved botanical illustration. His extraordinarily gifted engraver was Georg Dionysus Ehret (1708–70), whose task had been to complete 1,000 illustrations in 12 months. In the event he completed 500 before a falling out with his employer over his fee led to their separation. Ehret, we should note, worked with Carl Linnaeus and was sought out by Joseph Banks. Meissen used the images from the Iconography for a 2000-piece dinner service.

Do you want to know what a florilegium is, or a herbal, and would you like to acquire a piece of an undisputed monument in this genre of books? If so, you could be looking for Johann Wilhelm Weinmann’s Iconography of Plants and Flowers to the Life, or Conspectus of some Thousands of Plants, Trees, Shrubs, Flowers Fruits, Fungi, etc both Native and Foreign. But be aware: this publication consists of four (or sometimes eight) folio volumes, the first appearing in 1737 with a commentary in Latin (then the language of the learned) and German. It was compiled by a Bavarian apothecary, Johann Weinmann (1683–1744), who was probably the first to use a colour mezzotint method of engraved botanical illustration. His extraordinarily gifted engraver was Georg Dionysus Ehret (1708–70), whose task had been to complete 1,000 illustrations in 12 months. In the event he completed 500 before a falling out with his employer over his fee led to their separation. Ehret, we should note, worked with Carl Linnaeus and was sought out by Joseph Banks. Meissen used the images from the Iconography for a 2000-piece dinner service.

In 18th-century Europe the encyclopaedia was adored: one thinks of Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary, the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Burney’s History of Music. They were huge undertakings. Similarly, everything about Weinmann’s massive botanical publication was gigantic. If today you were to stagger home from the auction with your four- or eight-volume set of his Phytanthoza Iconographia you might keep quiet about its cost price, withheld after auction because it fetched double the asking price. You might admit to your botanical friends that the first volume alone recently sold for $US 6,000 and a single plate from it came in at nearly £400.

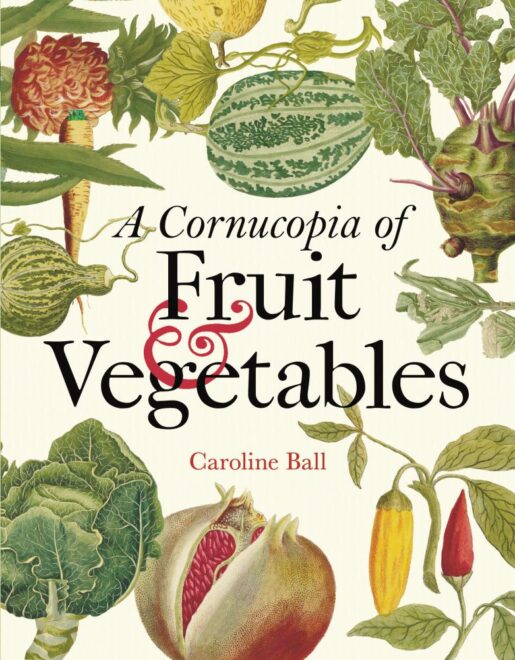

Alternatively and happily there is Caroline Ball’s A Cornucopia of Fruit and Vegetables: Illustrations from an Eighteenth-Century Botanical Treasury (Bodleian Library, Oxford, 2021). After an attractive 30-page introduction providing the historical context and some fascinating biographical notes, there are more than 100 annotated pages of images reproduced from Weinmann’s Iconography. In all, half a kilo of botanical delights, both edible and decorative, for a manageable $29.99 For this you will see –– in 18th-century colours and textures – squashes, gourds, apples, pears, hops, melons, mulberry, pea, carrot, blackberry, coconut, banana, apricots, spinach, tomato, onions, orach, lettuce, cherry, beans and much more.

The names of Weinmann’s several assistants in his massive project (Seuter, Ridinger and Haid) appear on the 1737 title page, but that of his engraver, Georg Ehret does not. Nevertheless, today, Ball tells us, his name is ‘uttered with awe by botanical artists and art historians, and he is considered one of the very finest illustrators from a golden age of botanical art’ (p. 22). Her selection of Weinemann/Ehret’s work shows where the florilegium’s roots are and she provides a key to each of the plates and a guide to further reading.

In Australia, the florilegium genre is alive and well, as Colleen Morris and Louisa Murray’s splendid The Florilegium of Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens (2016) shows. For a botanical enthusiast this modest sampling of Weinemann’s vast work would make a welcome gift, both to give or receive. It is in English, it is portable, it is affordable, it is in full colour, and it will fit on your bookshelf or coffee-table. The Iconography was both a florilegium and a herbal and comes to us from a time when everything was to be discovered, labelled, ordered and recorded: as this sampling indicates, it was also an age of great books, the medium of such learning.

Reviewer Clive Probyn, AGHS Southern Highlands