Reviewed by John Dwyer, QC, PhD

This book is disappointing in a number of ways. Its intent was ‘to revive the work of late 19th century landscape photographers that shaped the environmental attitudes of settlers in the colonies of the Tasman World and in California’. These photographers, the publisher, University of California Press, says ‘developed remarkably similar visions of nature. They rode a wave of interest in wilderness imagery and made pictures that were hung in settler drawing rooms, perused in albums, projected in theaters, and re-created on vacations.’

I had therefore expected Hore, an environmental historian and co-director of the New Earth Histories Research Program at University of New South Wales, would increase my understanding of landscapes and history. He did neither. The sub-title is ‘How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism’, but I did not find any explanation as to how, merely repeated assertions.

To take just one example, Hore writes:

By the end of the 1860’s white settlers across the world were increasingly reckoning with the complicated environmental consequences of colonialism through landscape photography.

He does not explain how the photographs could constitute a reckoning, or what the environmental consequences were.

Hore considers photographs from New Zealand, Australia and California as having the same effects on settlers but does not have sufficient regard to the differences in the displacement of First Nations peoples in the different countries.

The photographs date from the 1860s to the end of the 19th century, except for a black-and-white copy of John Glover’s painting ‘Natives on the Ouse River, Van Diemen’s Land 1838’. However, in Australia at least, settler colonialism was for the most part done before the landscape photographs of which Hore writes were taken. Certainly the taking of First Nations peoples’ land was largely completed much earlier: by 1849 1049 squatters occupied nearly 17.7 million hectares in eastern Australia, their motivation primarily economic . As Banjo Patterson reminds us, by 1895 the squatter ‘mounted on his thoroughbred’ could call on the full force of the law, three troopers, to protect his property.

The prose is not easy to read. The author uses expressions like ‘the conceit of wilderness’ but does not explain what he means. When he writes that photographers ‘perfected a kind of environmental image-making and storytelling that exuded territoriality,’ It is difficult to know how this oozing can be associated with the photographs.

For a book centred around photography, many of the images are disappointingly small, so that it is difficult to see what effects the photographer was trying to achieve or how they could possibly have shaped settler colonialism. It was an interesting idea to compare images from Australia, New Zealand and North America but the claim of a common agenda seems forced. Of the 53 illustrations, only four are of scenes on the Australian mainland.

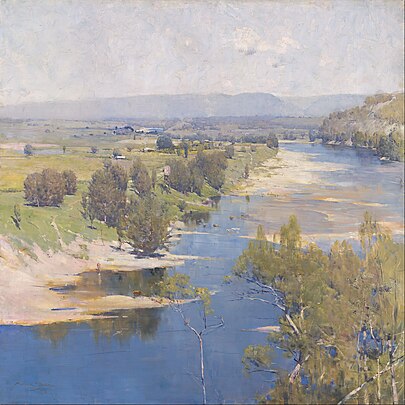

Hore writes that the 1890s were ‘a decade in which depictions of wilderness in Australian Romantic painting went into terminal decline and were replaced by photographic visions of nature’, a claim that can hardly be substantiated having regard to the works of painters such as Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Eugene von Guerard and Frederick McCubbin, to name just a few.

(Dwyer’s doctoral thesis is titled ‘Weeds in Victorian Landscapes’)

Visions of Nature, How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism (University of California Press, 2022) by Jarod Hore received the Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand Studies Network Donna Coates Prize 2022, the Australian Historical Association’s Marilyn Lake Prize for Australian Transnational History 2023 and has been shortlisted for the NSW Premiers’ History Awards, General History Category.