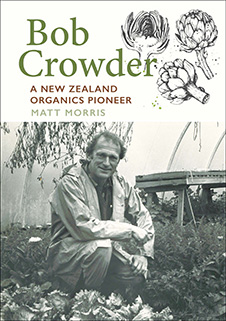

Stuart Read reviews Bob Crowder: a New Zealand organics pioneer, by Matt Morris, Otago University Press, 2024

This is a quiet landmark book from over the ditch. About an industry – organic farming − that’s now mainstream and worth big bucks but, for a long time, ridiculed as ‘cranky’ and ‘lunatic fringe’. And about a man who flew under the radar yet had a huge impact, beyond organics alone.

I got to know Bob at Lincoln University as a shorts-wearing, no-tie practical academic, whose casual style and radical biodynamic orchard (ablaze with 1.5m+ high rich ‘ley meadow’ understorey to encourage natural predators for pests of apples, pears and more) seemed strange, exciting. His ‘coppice demonstration plots’ taught farmers about alternative sources of income, shelter and actively managing wood-crops – carbon-farming: innovative thinking and practical action. I was fortunate to overlap with him – he retired from teaching in 1997.

Crowder was a lecturer in horticulture at Lincoln College (later, University) in Canterbury, after working for a time as an extension officer of the NZ Department of Agriculture & Fisheries, in south Auckland. An Englishman, he was won over by the emerging organic movement, increasingly coming to question the orthodoxy of rampant post-Second World War chemical use on crops, and the industrialisation/mechanisation of the agri-/horticultural industries. With a scientist’s mind, he set out to do systematic research to demonstrate that not using masses of chemicals could be equally productive and equally competitive in domestic and export markets. He showed that building soil structure and biological diversity was ‘win:win’ for all.

He joined Lincoln in 1966, when it was diversifying away from strict agriculture into horticulture – as was Massey University (Palmerston North, North Island). It was significant for New Zealand to diversify away from meat, wool, and milk, and compete in an international environment that was rapidly mechanising, industrialising and getting more exact, with gear-like Wilcox’s Stanhay precision (seed) drills, for example. Pushing commercial (intensive cropping) horticulture as a career choice was government policy. Bob established a Horticultural Research Area at the college, in late 1967, with an agenda of testing new crops, growing, weed and pest control and harvesting techniques, as well as , building the evidence base for the sector.

Crowder was instrumental in developing an industry now worth hundreds of millions of dollars in income, not least from exports. From 1991’s $1.5m (under 0.1% of its agricultural production, NZ organic exports were worth $40m by 1997, with 25 per cent growth rates in the US, Europe and Japan, whose markets were consumer-and market-led.

As one of organics (and biodynamics – another early name) first advocates, Crowder developed the first NZ organics research unit at Lincoln, its Biological Husbandry Unit. This provided hands-on experience for students, demonstration plots for farmers and growers to visit, see, question. He fought for years to get broad institutional support.

By building links with like-minded advocates and leaders around the world – California, Europe, and the UK − Crowder had an impact beyond New Zealand.. He developed connections with organic research units overseas and international organics institutions, not least the International Forum of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM, started in 1972, in France to coordinate global efforts in organics and, at first, heavily Eurocentric. He joined IFOAM in 1981, started attending its conferences and presenting New Zealand as a front-runner and early champion in what now is coined ‘sustainable agriculture’. He was a corresponding Board member of IFOAM’s technical committee, from 1988 to 1992. IFOAM would set and encourage worldwide standards for ‘organic’ inspection and accreditation schemes. Definitions and standards mattered.

Crowder organised an IFOAM tour of inspection of New Zealand in 1988, inviting interested Aussies to observe. The National Association for Sustainable Agriculture, Australia (NASAA) subsequently joined IFOAM in 1995. IFOAM awarded Crowder its Recognition Award in 1993 for his ‘international contribution to biological husbandry’ and, with his help, in 1994 held its international conference at Lincoln. This was a tremendous success, spotlighting New Zealand’s progress. A long and hard ‘sell’ to governments, bureaucrats, and farmers finally paid off. Statistics, proof, competitive credibility mattered.

All this came at high personal cost – Crowder was gay, well before that was legal or tolerated. He was also strong-minded and at times argumentative. He ruffled feathers in a conservative sector, often ill-inclined to question. And he was larger than life: Crowder was my introduction to Morris Dancing – he set up a side (a group) in 1976 in Christchurch, thus reviving it (it had died out in the 1930s in Christchurch, in the 1940s over NZ). He and his ‘Erewhon Morris’ side appeared on ‘Opportunity Knocks’ on NZ TV in 1977. Labelled (and boxed as) an ‘eccentric,’ Crowder was sidelined by some, which limited his institutional backing for years. Looking back, it is obvious that, despite this, he showed extraordinary courage and leadership. Fostering others also mattered.

To quote Lincoln’s Professor Richard Rowe (head of horticulture, 1979+), writing to the Fruitgrowers Federation:

Mr Crowder in my opinion has done more individually to protect New Zealand’s clean green image in world forums than any New Zealander.

The author of this biography is Matt Morris, a garden historian – his 2021 book Common Ground: Garden Histories of Aoteoroa is well worth seeking out. He does a complex man justice : it fleshes out Crowder’s English childhood and background, social and private lives, public persona, achievements after emigrating to NZ in the 1960s, and disappointments.

The author of this biography is Matt Morris, a garden historian – his 2021 book Common Ground: Garden Histories of Aoteoroa is well worth seeking out. He does a complex man justice : it fleshes out Crowder’s English childhood and background, social and private lives, public persona, achievements after emigrating to NZ in the 1960s, and disappointments.

This is a fascinating book – chronicling radical movements and social change over the last 50 years – from much-derided ‘organic’ to supermarket sections thatproudly trumpet ‘certified organic’. How much has changed for today’s health-conscious shopper and diet, not to mention to concern about ecosystems, carbon miles and global sustainability. It pays tribute to ‘bottom-up’ community-led change, which governments so often follow, once pushed to do so. Do read this book.