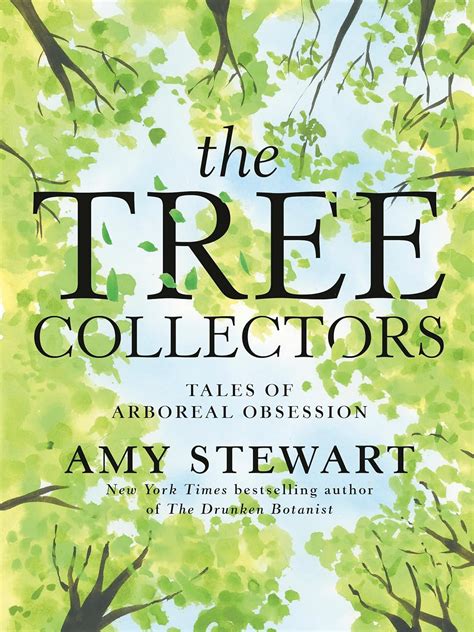

Amy Stewart, The Tree Collectors, Tales of Arboreal Obsession, Text Publishing, Melbourne, Australia. 2023, 307 pp.

Collecting or putting together a collection of something is a common habit. About 30 to 40% of households engage in some form of collecting behaviour. A huge range of things can be collected − so why not trees and plants?

This book, written and illustrated by Amy Stewart, recounts the stories of 50 people with a passion for botanical collecting. Amy Stewart now lives in Portland, Oregon. She has written several non-fiction books on the natural world including Wicked Bugs, Wicked Plants and the New York Times best seller, the Drunken Botanist, which covers 150 plants that have been fermented and distilled somewhere in history. No doubt she met some of te subjects of this book while researching those others.

Of course, there have been many theories to explain why people collect, from Freud relating it to toilet training behaviour to others blaming damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex of the brain. Maybe this is true of compulsive hoarders but for most of us it just gives a better sense of self and achievement. Stewart examines the reasons of 50 collectors for amassing a collection of trees and other plant materials and how their lives have been transformed. Her book covers many unusual collections and collectors who have had to adapt because of a lack of space and/or an inappropriate climate. Are they pathological in their pursuits as Freud would have suggested? Some of them get pretty close, such as Dave Adams who lives in Boise, Idaho where in winter it gets to minus 30ºC with 30 to 45 cm of snow. Palm trees would seem a poor choice to collect but he grows them in pots so they can be moved indoors under artificial light when it freezes. Then there is Sam van Aken who has grafted 40 different stone fruit varieties (apricots, almonds, plums, cherries, peaches and nectarines) on the one understock. Most collectors do end up pushing the boundaries a little: maybe both these two people have gone a little too far.

In the introduction, Stewart explains how she came to write on the subject and provides a few anecdotes from the chapters. I like the quote from Beth Edward, a magnolia collector, who said,

No one else that I know in my career, or even my family, really shares this interest of mine. I’m the only one. When I’m with people in the Magnolia Society, I’m just another person. I’m normal.

As Stewart says, there seems to be a plant society for just about everything and collectors love to be with other collectors.

Each of the 50 collectors is presented as a complete chapter but they are grouped, often tenuously, into loose categories such as Healers, Ecologists, Artists, Curators and so on. Not all the collections are what one would anticipate. They include leaves, pinecones, wood or seed. There are also collections in unusual places such as beside freeways or small plots of unused land. Some people see their role is to record and catalogue expansive collections of trees in public areas such as Stanford University.

In Reagan Wytsalucy’s case, her aim is to develop a bridge with her ancestors by trying to bring the Navajo peach back into cultivation. This peach was a vital part of Navajo life but was almost wiped out in the 1860s by the US army when it drove the Navajo from their lands. Only a handful of trees survived and now Wytsalucy is collecting and distributing them for reintroduction.

Stories of the more typical, yet truly diverse, obsessive collectors are also included. These collectors are known as completists or completionists and aim to collect every item in a set. The archetype is Dean Nicolle with his collection of eucalyptus species at Currency Creek Arboretum in South Australia. Nicolle has grown or tried to grow around 950 species of eucalyptus: that says it all.

Overall, the book is easy to read, and the people and their collections are of interest to the botanically minded. I would, however, have liked greater depth. Some of the people I know personally and can confirm their passion for collecting. Their stories could have been explored more fully. Similarly, though beautifully illustrated by the author, the addition of photographs of many of the collections would have been beneficial.

While we tree collectors need little encouragement, reading this book will make us feel more normal.

Simon Grant OAM, (Acting) President of The International Maple Society and Vice President, International Dendrology Society, Australia