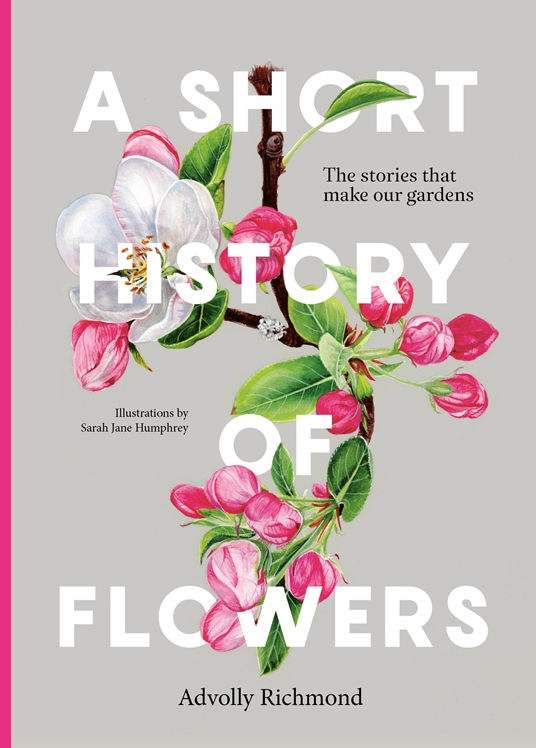

Michaela Hill reviews A Short History of Flowers, The stories that make our gardens by Advolly Richmond, illustrations by Sarah Jane Humphrey (Frances Lincoln 2024).

This book may just be the perfect last-minute Christmas shop. It will appeal to gardeners, plant enthusiasts, artists and lovers of plant histories. While its scope is European, primarily English, lovers of Australian plants will find much to uncover and learn about the plants. The author has taken 60 fairly ordinary garden plants and provided the background of their introduction to the British Isles.

Richmond has filled in the gaps and added details from new research on the origin, uses and naming of these everyday plants. The bearded iris, Iris germanica, was cultivated in monasteries for the production of green pigment used in illuminated manuscripts, for example. Featured also is the bougainvillea, Bougainvillea spectabilis, a co-star of AGHS’s Ipswich 2023 conference, with credit for its ‘discovery’ being given to the 18th century female botanist-in-disguise, Jeanne Baret, a semi-stowaway on Bougainville’s journeys.

This book is more than a modern re-working of some personal plant favourites. The histories of the collectors, the botanists and their patrons are deftly woven into the short narratives on each flower. The role of lesser known botanical artists and gardeners, such as African–American folk artist Clementine Hunter (1887–1988) and the West-African ex-slave John Ystumllyn, Britain’s first well-recorded Black horticulturist in North Wales after whom a recently launched yellow rose has been named.

Richmond writes as a gardener and plant lover. The meaning of a flower, much considered in Victorian times, is wryly examined. Since popularity does not always travel well with time, the invasive status of several of the plants in the book is not ignored. One example, a native of Gibraltar, the Rhododendron ponticum, was treated early on as a tender exotic, of appeal to those of generous means. In 1880s plant catalogues its price was not even quoted. Wealthy Victorian landowners discovered that the plant self-seeded freely and, initially, encouraged this habit. Today English legislation makes it illegal to plant it in the wild or to allow it to encroach into areas beyond your property.

The Australian everlasting, Xerochrysum bracteatum syn. Helichrysum bracteatum, collected on Baudin’s 1800 expedition to Australia, is featured. The everlasting’s paper-like composition and long life made it ideal for Victorian parlour dome arrangements, to be bequeathed to unlucky distant relatives, the author suggests. It’s unlikely that this book will suffer the same fate.

The context Richmond offers makes A Short History of Flowers the sort of volume that is handy for remembering plant names and forms. Sarah Jane Humphrey’s coloured illustrations of each flower add handsomely to this book. It is a keeper for plant historians and their friends.